Audio Version:

Day Thirty-Five by Sandra Gail Lambert

On September 7, 1940 a twenty-mile swath of bombers and their accompanying fighters flew from Germany, over the English Channel, and on to London. The nine hundred and sixty five planes bombed the city. The raids continued for fifty-seven consecutive days. One million bombs were dropped.

Jostled by neighbors carrying bulky sleeping bags and children and suitcases of precious things, Lena and Yvonne climb the concrete steps. They have spent the night in the tube station. Mother and daughter, arm in arm, they rise towards the grey light above them. They pause at the top. A snow of ash, cotton ticking, and feathers tumbles through the air and, mixed with fog and the scent of burnt asphalt, clings to their sweaters. Somewhere there is fire. Somewhere close there will be a home whose mattresses and pillows have been exploded out of windows. A siren signals the all clear.

Yvonne rushes ahead of her mother, and her gait is a fourteen-year-old mixture of languid woman and bony-kneed gallop. Lena calls her daughter back to her side and teaches by example the brisk walk that is just as fast, but gives no outward sign of panic. They move through the debris on the narrow streets, through the crowds of tired people all doing their own brisk walks, all not quite breathing until they reach the corner that will give them the first view of their own homes. Before Lena and Yvonne arrive at theirs, a man in a steel helmet intercepts them. It wasn’t ours. Bernard says this close to the ears of his wife and daughter. It's cruel to announce good fortune. He walks a little way with them, telling light-hearted stories about his night watch, about helping a dog give birth, about the dotty old woman who left her curtains open again. I’m going to have a cup of tea at the warden post. I’ll be home to change for work. Lena and Yvonne watch him disappear into a cloud of smoke.

They turn their corner and get the first glimpse. Each house in the row is still attached to the one beside it, and not a single grime-stained brick is thrown into the street. No windows are shattered onto the rose beds underneath them. Lena and Yvonne have developed a routine. Yvonne goes through the house by feel, past the still blacked-out windows, to the bathroom in the back garden. Lena stokes the stove and fills a pot for tea. She sets out three precious eggs to boil and slices the hard end of a loaf. They pass in the hall. Yvonne goes up the narrow stairs to her bedroom where she pulls back the drapes and dresses for school in the thin light. Soon she hears her mother climb the stairs, humming, ready to change into overalls for her factory job. Yvonne is in front of the mirror, trying out a new hairstyle, when her mother screams. She rushes to her parents’ bedroom, the brush still gripped in one hand.

It’s too light, is her first thought. Then she sees the hole in the roof over the bed and goes to her mother, touches her arm. Lena isn’t staring at the ceiling. Yvonne follows her gaze to the bed, and the brush drops from her hand. They both jerk as it hits and bounces twice on the floorboards, but don’t look away from the bed. The eiderdown comforter is piled high at the edges, almost covering the deep indentation in its center. Lena leans over the bed, putting one hand on her daughter’s chest to push her back. She sees a length of metallic grey, fat in the middle and tapered to fins at the end—a parody of a person sleeping. She bends to look under the bed. The slats are broken and the mattress is pushed to within an inch of the floor.

Darling, run. Find your father. Lena whispers to her daughter without turning. Yvonne races into the street and ignores the concerned shouts of the neighbors as she runs full-out to the tea shop where her father finishes up his shift. His team are spread out over chairs, yawning, naming the stores they saw looted the night before. Yvonne falls at Bernard’s feet, causing tea to slosh into its saucer. He and his shift listen to her breathless story, and the men have collected their gear before she finishes. Yvonne leaves before Bernard can stop her. She stays ahead of the men and calls to her mother as she reaches the still open door. She runs lightly up the stairs. Lena has not moved. Yvonne takes her by the hand and lifts her to her feet, turning them away from the ersatz sleeper. Lena and Yvonne both take things as they leave the house. Lena, her husband’s medals from the Great War that lie next to the washstand and a tintype of her own mother that hangs on the wall of the stairway. Yvonne, a music box topped with a couple dancing that sits on the entryway table and her favorite hat from the coat rack by the door.

Bernard and his men pass them at the door. He points wordlessly up the street. Lena and Yvonne walk to the first corner before they stop and turn. Their neighbors evacuate their own homes and gather around. They are silent, except for the one that can never be quiet. The never-quiet man’s voice blurs around them and their annoyance with him comforts and bonds them. Then they hear laughing and the tail end of a tasteless joke. Pushing through the doorway, too many at once, the men swagger into the street. Four of them bear a weighted sling out the door and into a panel truck. Bernard shakes hands all around and waves to his family. It’s all over, come back.

Lena and Yvonne and Bernard sit at their kitchen table. The teakettle is steaming. The medals, the picture, the hat, and the music box are scattered over the table between the bread plate and the soft-boiled eggs waiting in their cups. Bernard slices the top off his with one neat stroke of a knife. Yvonne turns the key under the music box and the couple turns this way and that. Lena sings the words to the tune. Pack up all my cares and woe, here I go, singing low. Yvonne and Bernard join her for the chorus. Bye-bye blackbird, bye-bye.

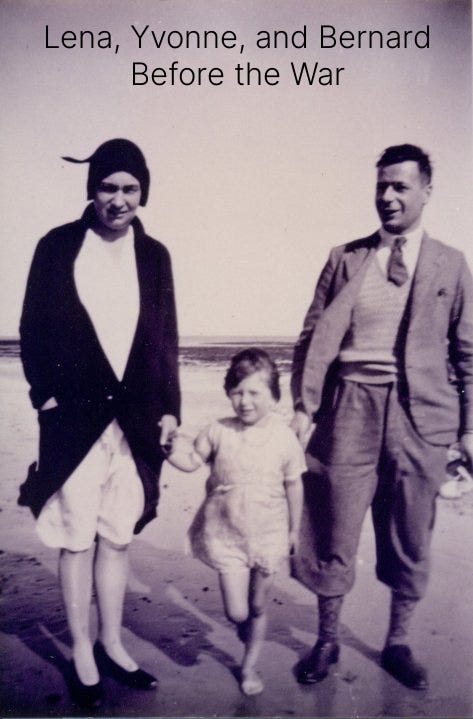

This story of a bomb in my grandparent's bed is, as are most family stories, truth embellished with fiction of both my mother's and my invention. My mother told the story with an emphasis on the bomb. But I am distanced from her experience of passing by daily destruction, bedding thrown out in the streets, and what must have been the smell of burnt feathers. For me the story is about emerging.

We watch emergings on television. The aerial views of students stumbling away from a building with their hands behind their heads. A reporter tripping among debris to interview a survivor of a tornado as they pick through remains for something, anything. Our held breaths as we count the running, hunched down figures escaping from a synagogue. The huddles of despair as we wait too long for the survivors of the shooting at a gay bar to appear.

World War II London had an etiquette for the morning after a night of bombing. The unspoken rules were don't run or push, don't shout your relief or thank god when you find your home intact, don't collapse in wailing grief if it isn't. These behaviors were deemed unseemly and inconsiderate of other people in their own possible suffering. Even seventy years later my mother had disdain for people not "handling" themselves during a crisis. But when the nightly news hour broadcast bombings from Vietnam to Iraq, she would go to kitchen, pour a drink, light another cigarette, and fry slices of SPAM. It had been welcome protein during the long years of rationing. It comforted her.

In the United States we are mostly the ones who bomb. But still, our "mornings after" are increasing what with frequent climate change-induced disasters and so many mass shootings that the media now picks and chooses which ones to report on. Many communities and people because of racism, geographic remoteness, or age and disability know we will be considered last, if ever. We've known this for a while. We've come to understand that first responders are not the police, fire fighters, or even the paramedics. We who are emerging are the first responders. What can we learn from each other? Can we collaborate? How do we develop an etiquette of useful compassion?

Addendum: The origins of this essay. Or is it fiction? Both?

My mother seldom told us about her life during WWII, but she took a class at her senior living center where they recorded cassette tapes about their lives to give to their children. Even before the tape arrived in the mail, she called and told me she’d made up or left out parts. Like the story about her Uncle who’d died along with a hundred other people when a London subway shelter collapsed from the shelling. She whispered (over the phone, she alone in her house, me alone in my apartment) that she’d left out that the reason he was in that shelter was because he’d deserted and no one in the family would take him in. And I knew from experience that my mother both embellished and obfuscated events that happened the week before much less fifty years ago.

Which meant that when I took my own class where the instructor asked us to use a family memory, legend, tall tale, or myth and turn it into fiction, I knew my mother’s story about the bomb in her parents bed was most likely already many times removed from fact.

Yet, I’ve included it in an upcoming collection of essays. Even though it was published as fiction by New Letters many years ago. I tell myself I get to because I’ve added fancy essay stuff like paragraphs that analyze the implications of what happened or reflect on the lessons offered to our current situations. But also, it’s a reminder.

I don’t think my mother ever thought, “I’m going to lie about this part to make myself come off better,” or consciously decided something was private and no one else’s business. It was a cultural norm, an automatic reflex, a survival strategy. Yet, I’ve disrupted this part of my inheritance by writing personal essays. I talk out loud about how I get to keep whatever I want to private. But more and more, as I age, I am my mother’s daughter. So this essay or family legend or myth makes me ask the questions. What do I embellish? What do I change to make myself seem like a better or more interesting person? When have I just full on lied?

Sandra, as I age I am more and more my sister's sister! I used to hate the "look at me" mode that dominated in our family. But when I began writing my blog (The Feminist Grandma) I found myself exposing more and more, even including a picture of me exercising to Richard Simmons video in underpants and tshirt (an unedifying sight). Then when Luli died a lot of her seemed to enter me, and I became more and more show-offy and outlandish. It amuses and puzzled me.

I just finished The Night Watch, by Sarah Waters, so it was startling to be back again, in that horror, transported by YOUR brilliant writing. As for the truth, all of it was true for someone.